By John Perse

Could it be possible that a billboard in Cleveland, Ohio placed there in July 1964 by a car dealer actually set the stage for the Water Quality Act in 1965, the Environmental Defense Fund in 1967, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act in 1968, and ultimately, the Environmental Protection Act in 1970?

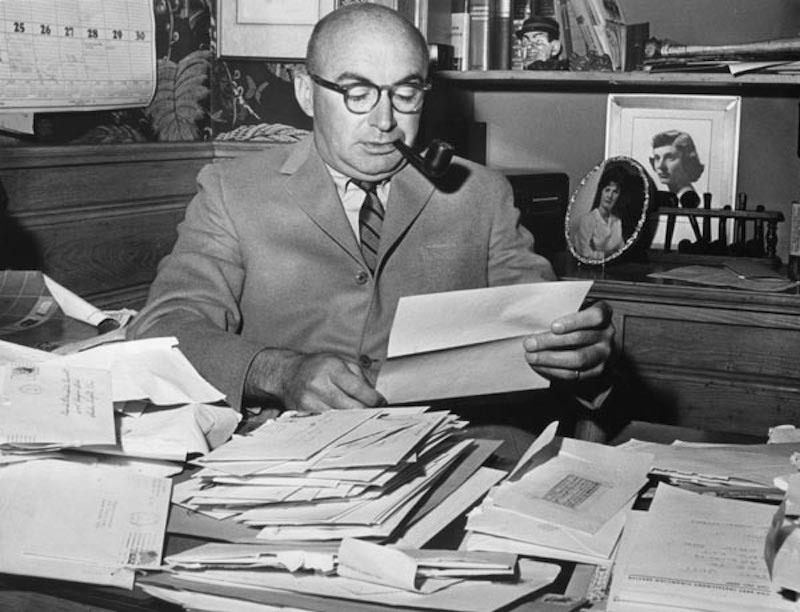

In fact, a former area car dealer, who also happened to be an environmental activist named David Blaushild (1916 – 1979) was instrumental in bringing attention to the plight and blight of Lake Erie. Having witnessed the pollution in lakes and streams in his own Shaker Heights neighborhood – as well as the inefficiencies of the local sewage systems which, after heavy rains, often dumped raw sewage into the local water ways – Blaushild sprang into action. At the time, Lake Erie also happened to be the final “resting place” for industrial chemical waste from local industries located along the industrial valley of the Cuyahoga River.

Blaushild used his showmanship and salesperson skills to bring this crisis to light and build a base of support that could influence policymakers. His method of bringing attention was somewhat unusual in that as an owner of a car dealership, he was well positioned to use billboard advertising as a way of promulgating his messages regarding the pollution in Lake Erie. Blaushild also booked television appearances, radio interviews and a speaking tour to spread his message. Local newspapers similarly began to call on lawmakers to act on water pollution issues.

A series of advertisements in Cleveland’s newspapers complemented the imposing signage and called on the citizenry to join the crusade. Blaushild asked Clevelanders to express their support for the cause by filling out and mailing in a coupon to his car dealership, which would be forwarded to public officials. An overflow of public response prompted Blaushild to expand his efforts by sending both petitions and an anti-pollution resolution to those that replied to his ads. The respondents could then circulate the petitions within their communities throughout the greater Cleveland area and submit the petitions to local governing bodies for adoption. By some accounts, over half a million signatures were gathered between June and August 1964. Twenty-six towns along Lake Erie passed Blaushild’s resolution calling on Ohio Governor James Rhodes to take steps towards preventing industrial and sanitary pollution from reaching public waters.

Not only did Blaushild rally the public to inundate local civic leaders, he also became a Shaker Heights councilman and introduced a bill banning use of DDT in his community.

Thanks to the vigor, insight, creativity and concern of a local businessman who decided that he had seen enough, one Cleveland roadside billboard with the message “Let’s Stop Killing Lake Erie” could be said to have been the catalyst for a national environmental protection movement.