And the Fight for Indigenous Rights in Northeast Ohio

By John Perse

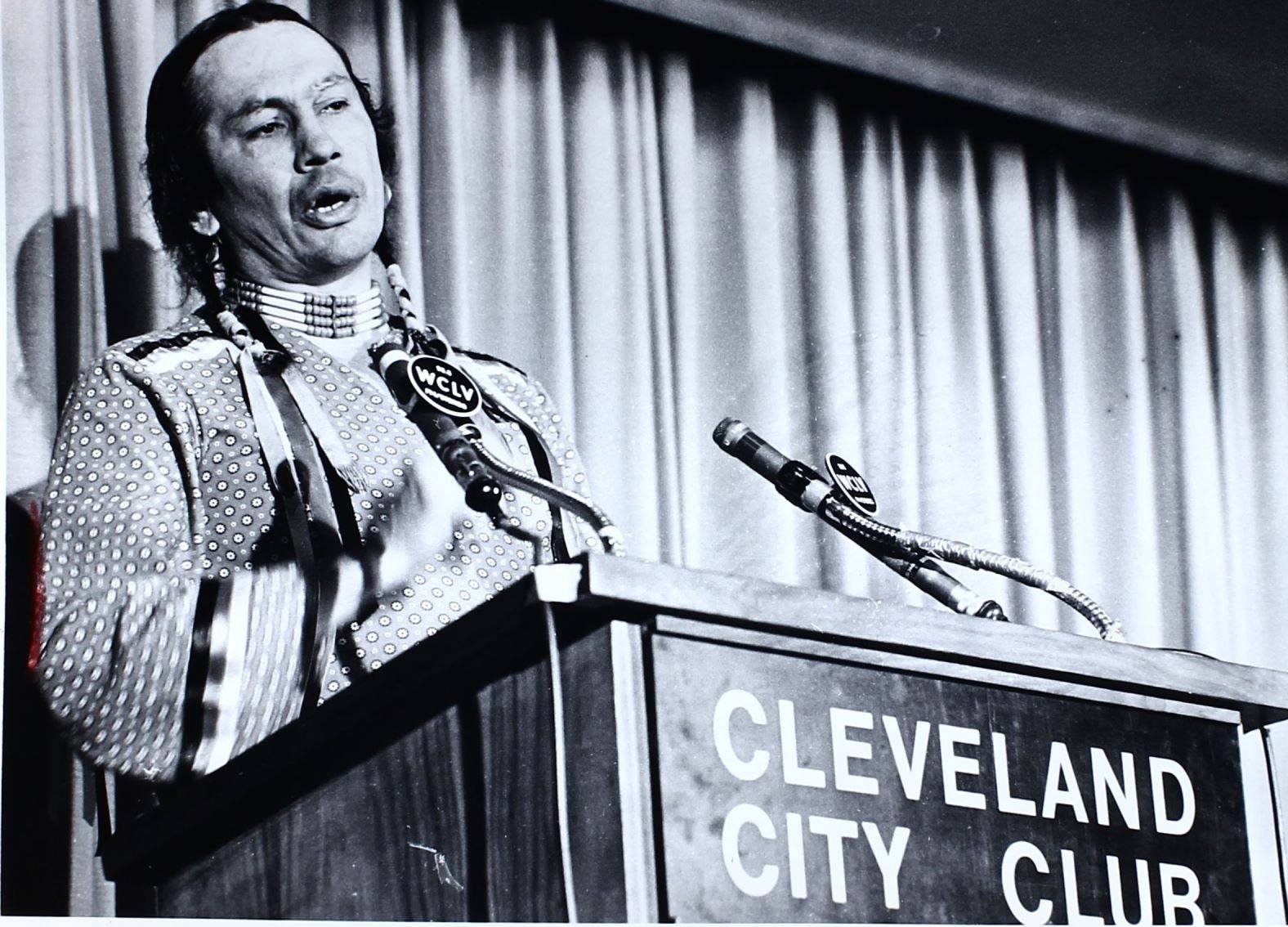

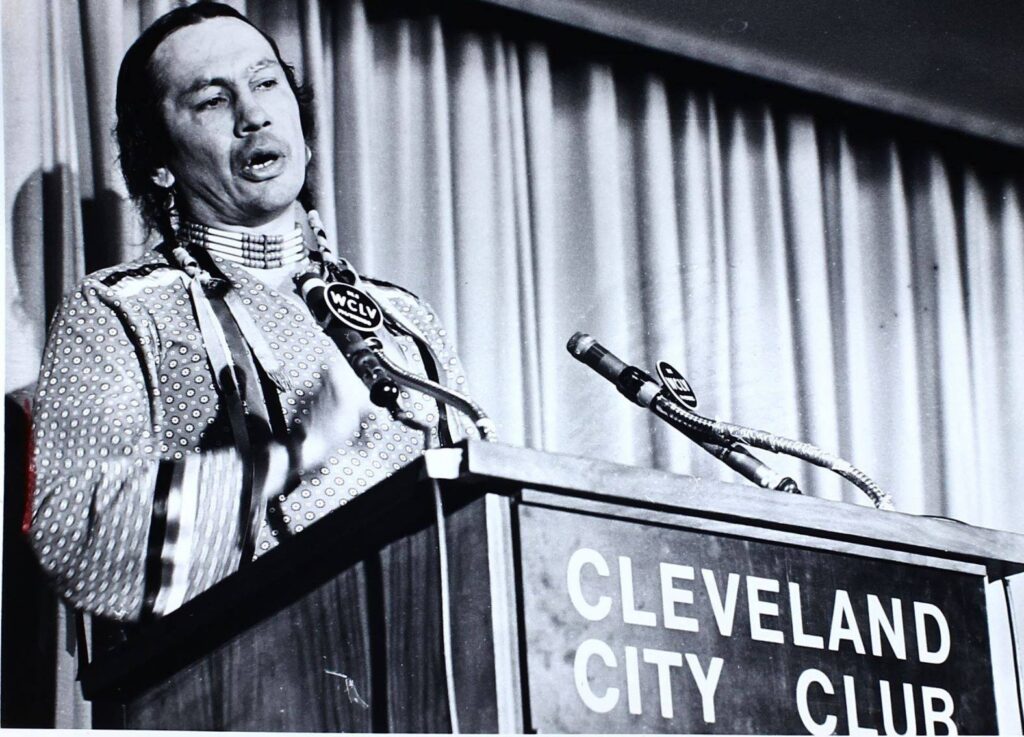

While he was not born or raised in Cleveland, civil rights activist Russell Means played an integral role in the local Native community of Northeast Ohio. Determined, unrelenting, proud, confrontational, and quite controversial, Means (1938 – 2012) was a civil rights activist, writer, and a leader of the American Indian Movement (AIM). Founded in 1968 at the height of the counterculture / civil rights era, AIM sought to address systemic issues of poverty, discrimination, and police brutality against Natives, particularly in U.S. cities. The Movement eventually focused on historic treaty rights, high rates of unemployment, the lack of American Indian subjects in education, and the preservation of Indigenous cultures.

A Lakota Native, Means was born on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, but grew up mostly in San Francisco. He lived on a number of reservations and eventually moved to Cleveland and founded the government-funded Cleveland American Indian Center in 1969. Natives had been moving to Cleveland since 1957 as a part of the federal government’s “relocation” program, but faced many difficulties. Indeed, “The cost to ‘relocated’ Indians was often steep: some adjusted but many others suffered economic hardship and overt discrimination after being abruptly disconnected from their cultures and plunged into an urban society that knew little about them.” 1

The center aimed to help Cleveland’s native American population adapt to urban life and opened as a cultural and social service center in the basement of St. John’s Episcopal Church.2 (Today, approximately 5,000 Natives live in the Greater Cleveland area.)

It was at this time serving as executive director of the American Indian Center that Means met the founders of AIM, which he joined at age 30. As a result of this connection, “Cleveland was one of the launching pads for the national Indian rights movement” (https://case.edu/ech/articles/m/means-russell) and sought to remedy the problems associated with the relocation to unfamiliar urban environments, far from family, traditions, and lacking on employment and educational opportunities.

In 1972, Means also filed a $9 million lawsuit against the Cleveland Indians baseball team for its use of “Chief Wahoo,” the team’s traditional mascot. According to Means, “Chief Wahoo” “… epitomizes the stereotyped images of the American Indian,” and “… attacks the cultural heritage of the American Indian and destroys Indian pride.” The $9 million lawsuit against the Cleveland Indians baseball club for its Chief Wahoo mascot was settled out of court in 1983 for $35,000.3

Although there is controversy surrounding many of Means’ activities, both here in Cleveland, and throughout the nation many years thereafter, Means has been described as “… more than a leader, and by many accounts, more than a man: he was a living example of the struggle of the First Nations people. Means fought against the violations of Native civil rights and stood for justice, pride and the traditions and cultural heritage of North America’s indigenous people. A leader, politician, actor, speaker, and activist, Means was a vibrant example of the pride held by the First Nations people; in many ways, he was the very definition of defiance against the system, and what it can accomplish.”4

A quote by Means sums up for many people his contributions to the cause of equality, equity, and opportunity: “Freedom is for everyone, whatever lifestyle they choose, as long as it’s peaceful and honest.”