The Cedar Apartments just after they opened. They were some of the first public housing developments in Cleveland. Via Cleveland Historical.

First and foremost – we don’t want to bury the lede – anyone interested in learning about the history of homelessness in Cleveland should know that author Daniel Kerr will be a guest at the City Club of Cleveland on June 7, 2024. You can purchase a ticket and learn more here.

As we at Teaching Cleveland often share with people, there were probably few cities in the U.S. that grew faster between the Civil War and the Great Depression than Cleveland, Ohio. When one thinks of the big picture of Cleveland history and the economy that would come to play a dominant role in the the U.S. industrial boom, one might think of the birth of the oil or steel industry, or the role that Clevelanders like Samuel Mather played in controlling Great Lakes shipping, or the chemical and paint industries that would emerge from the shores of the Cuyahoga River.

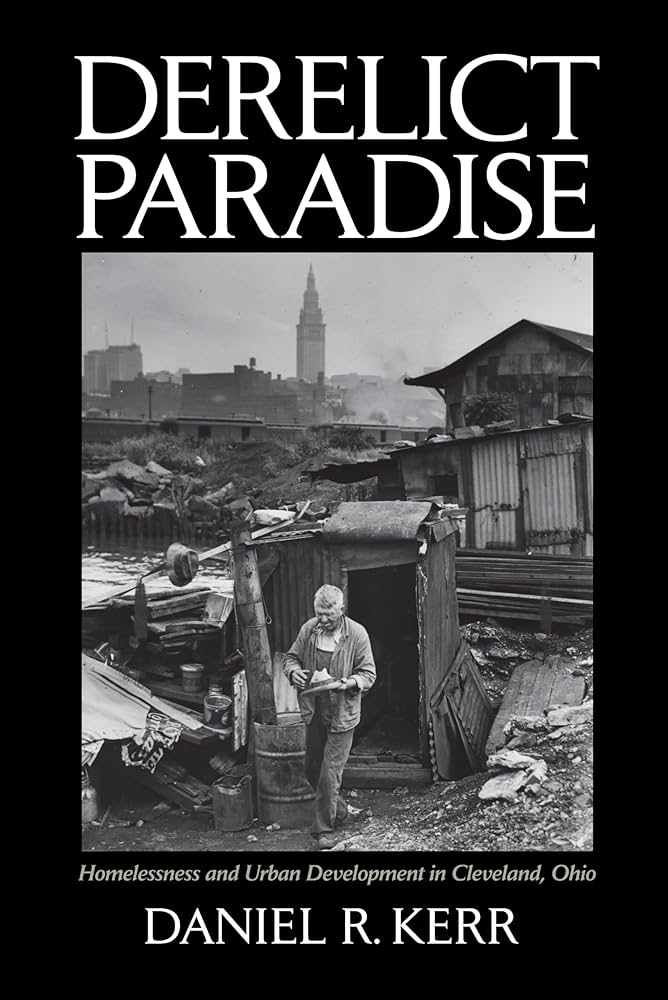

Daniel R. Kerr, in his book Derelict Paradise: Homelessness and Urban Development in Cleveland, Ohio, has provided another examination of Cleveland during that same period and beyond – one that examines the way tensions between industry and politics collided with those on the margins. His book traces the developments of the city and its institutions as its seemingly unbounded expansion ran headlong into laborers who struggled to create their own communities and the nearby working-class neighborhoods filled with individuals who provided the brawn behind the industrial boom.

As Kerr writes, the book is an attempt to understand the “historical roots of the entrenchment of homelessness in the city of Cleveland,” and along the way he provides fascinating detail about the individuals and organizations that emerged to support the unhoused and the unemployed. Today’s shelter system is in many ways the legacy of the conflicts among those on the margins and their advocates with many political and business leaders, for whom the presence of the unhoused and “slums” near downtown threatened to turn away more businesses and tourists.

In that era, many leaders of the progressive movement believed in “scientific charity” as a way to think about those on the margins and the challenges they experienced. This was a time when eugenics dominated academia and people’s general ideas about the worthiness of certain people. These ideas in part would create private organizations like the Associated Charities, which had begun in 1900, or the Wayfarer’s Lodge, which the Chamber of Commerce established at East 21st and Chester to house as many people as possible who were indigent.

And, a significant portion of Clevelanders struggled mightily, especially during the Great Depression. By 1931 one-third of Cleveland’s workforce faced unemployment, and the Black Cedar-Central neighborhood was hit the hardest. Of the 10 tracts with the highest unemployment rate, eight came from this neighborhood (and one tract had a 91.5 percent unemployment rate). Dotting the downtown area were “shantytowns,” “Hoovervilles,” “slums” – whatever one might call them.

Those who fought on behalf of the unhoused were numerous and well-organized. The Unemployed Council relied on demonstrations – some drawing tens of thousands like its May Day 1933 Public Square gathering – to highlight what they saw as the mean-spirited nature of the private Associated Charities. When the federal government began to establish a presence in local communities, social workers would eventually help to dismantle the private charity movement. Ultimately, widespread efforts at “slum clearance” would lead to public housing. The Outhwaite Homes, Cedar Apartments, and Lakeview Terrace would become the city’s first public housing projects, and would help to inform the strategies of the urban renewal era after World War II, which would profoundly shape the Greater Cleveland landscape.

So often our understanding of history comes through the lenses of organizations and people in official positions of power. Kerr’s book shares details of a history not often explored or discussed, and provides an opportunity for voices of the unhoused and their advocates to share their experiences through much of the 20th century in Cleveland. So often these histories are left out of our narratives and our consciousness – leaving our historical understanding bereft of the full scope of what has shaped our present day.