August L. Fluker retired in July 2021, following a 36-year career in architecture as principal at the Cleveland-based firm City Architecture. He has served as Principal/Managing Member at Fluker Consulting LLC since its inception in August 2021. In Cleveland, as well as statewide, Mr. Fluker has been recognized for his leadership and achievements. In 2009, he was appointed to the Board of Architects by Governor Ted Strickland. He has served on the city of Cleveland’s Planning Commission since 2018. Mr. Fluker serves as board member of the Partnership for Safer Cleveland, Cleveland Institute of Art, Baseball Heritage Museum, and New Village Corporation. Prior to forming Fluker Consulting LLC, Mr. Fluker was responsible for client contact, project management, and the administration and production of projects at City Architecture for 26 years. His experience and involvement range from large institutional projects to intimate storefront projects, and complex public transportation and infrastructure efforts. Mr. Fluker has dedicated the next chapter of his life to focus on people, context, and intentionality. His philosophy is to: Lead now. Steward critical conversations that promote responsive and responsible planning and design. One of the best parts about collaborating with Mr. Fluker is his dedication to teaching. His devotion to helping people around him be better is achieved in his own, unique way. Integrity is at his core in everything he does. His sense of humor, personal stories, and honest sharing collectively emphasize his knowledge while making friends and instilling confidence in those who work with him. He challenges the people and processes around him, challenging them to be better, to be more inquisitive and to be bold. One of Mr. Fluker’s first steps in his new role included serving as a coach for the first two cohorts of the Community Development Corporation Leadership Program, through the Jack, Joseph, and Morton Mandel Foundation. He always starts by asking: How do you change a place?

I grew up in the West Park area around West 117th and Bellaire. I attended Cleveland public schools. It was diverse. It was eclectic. One neighbor was Irish, the other was Lebanese. Over the years, it started becoming more African-American. When you started going north towards Lakewood and Halloran Park, we would be run off because of the color of our skin. We stayed pretty close to where we grew up.

My parents, my aunts and uncles, they all went to John Marshall High School. Up until my sophomore year, it was fine. It was about 80% white, 20% black. But when they started busing in 1978-1979, it was a totally different experience. Then it was more than 70-80% black. So they sort of flipped the table, and that’s when I started focusing on school because it was just a lot of unrest. The neighborhood folks didn’t really appreciate busing a lot of black folks into the community. It was kind of surreal – as we were walking into school, they would sit out on their porches and stoops and watch the buses.

My brother and I are about a year apart and they wanted to ship us to JFK (John F. Kennedy High School, in the Lee Harvard neighborhood on the east side). So my mother, we get on the rapid, we go down to the board of education, and she says, “It makes no sense, why are you shipping a black kid to the east side?” So, we stayed at John Marshall. There was a lot of civil unrest. My brother’s year, it got really bad. I think at least one or two people were shot, and there was a big strike. Everything came to a halt, which was nice, because it helped calm things down.

It was interesting because most of my friends were white, and what I was seeing was that a lot of the black kids were bullying some of my friends. So, I was known as an Uncle Tom because I protected my friends. I didn’t see color, right? That’s not how I was raised. It got to a point where I withdrew. It was like, “Finish, go home, repeat.” I didn’t even play sports.

In the 40s, both of my parents migrated to that neighborhood from Arkansas as small children with my grandparents. My family did a bit of research on why they came to that neighborhood. Allegedly, there was a train stop in Linndale. There’s a train overpass, and there used to be a train depot there. So, they got off there. I find that interesting because a lot of African Americnas, when the Great Migration happened, found themselves on the east side of the river. I don’t know whether it’s because my parents took the train in and said, “We’re not going to migrate anywhere else,” or what the reason was.

I attended Miami University, where I studied architecture. I came back to Cleveland, and my first job was as a concrete inspector with the City of Cleveland. I didn’t have any experience. No one would hire me, so I started inspecting concrete in Hough. That’s where I learned about neighborhoods, politics, and community development corporations. At the time, they were building Lexington Village. Councilwoman Fannie Lewis, at that time, had mobilized probably 100 residents who were picketing the project. That was Fannie. She had one great ability. She could rally her residents around anything that she thought might be worthy of their attention.

After that, I became friends with her. Our relationship went both ways. If I was OK, I was “August.” If I wasn’t OK, I was ‘Fluker.’

My first job in architecture was with Robert P. Madison. I also worked out of the Hough Partners in Progress office, the nonprofit that existed in Hough at the time, with a small architectural firm. That was before I started working for City Architecture.

After I married my wife Jennifer, we moved to Cleveland Heights for about three years, and then we built this house in 2000. My wife and I were committed to staying in the city. She was raised in the Lee-Harvard area. I was raised on the west side. We wanted to find a place that was affordable. At the time, Cleveland Heights was pretty expensive. This location was relatively close to her mom at the time. We looked at East Boulevard and a couple of other areas and found that they were building houses with incentives here.

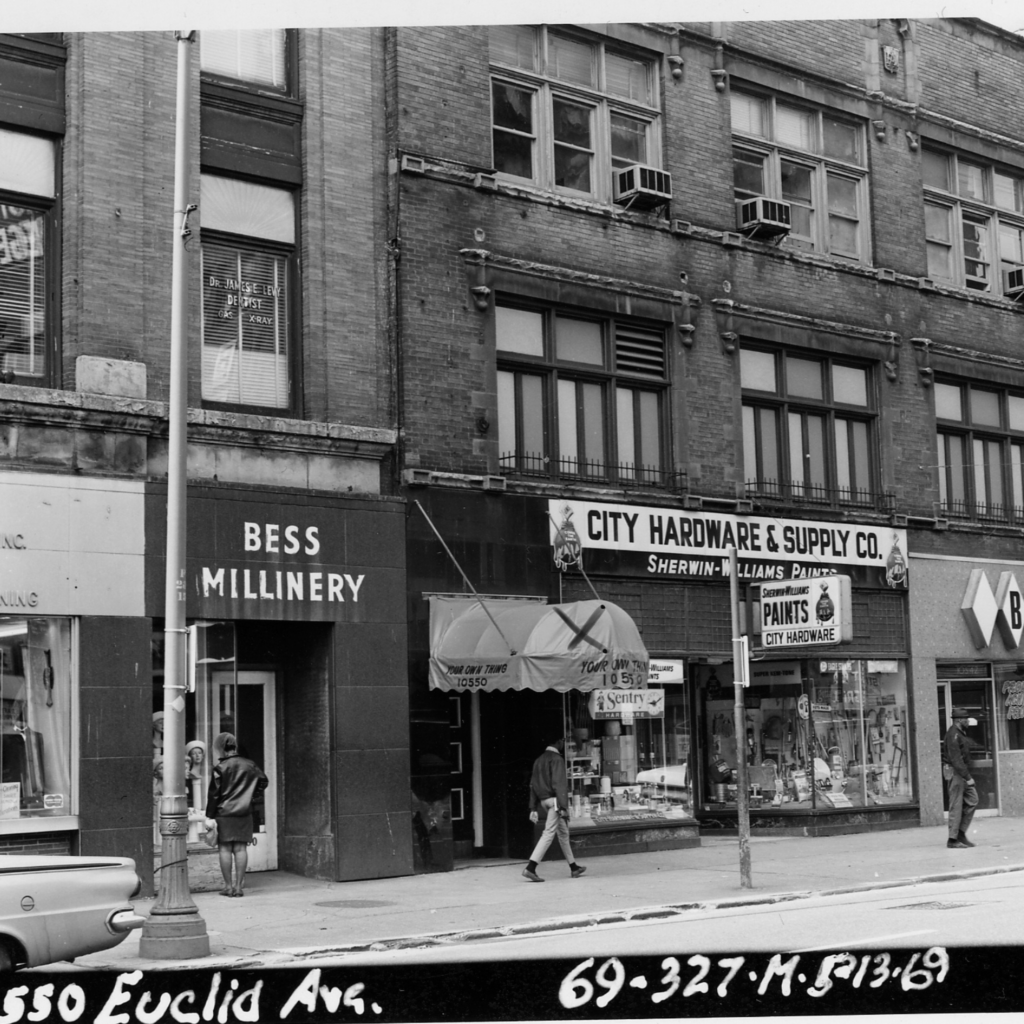

We were interested in having a Euclid Avenue address because of the history of Millionaire’s Row, and we knew at some time there would be a transportation line on Euclid. So, we put our money where our mouth was. The transportation line on Euclid Avenue didn’t happen until almost 10 years later, but we knew the two hubs of University Circle and Public Square, the two big employment districts, would eventually connect.

We didn’t get into this blindly. We would come down all times of day, weekend, weekday, night, and we knew what we were inheriting. You had to have vision. Not all this was here at that time. Do you remember Euclid Avenue then? It wasn’t pretty. It was a huge leap of faith. The Clinic, which is now almost at our front door, their footprint in 2000 was maybe 50% of what it is now.

But I knew that Fairfax Renaissance Development Corporation was planning other developments. When you do things like this, you’re creating the market. Zaremba built it. My firm designed it. That was one of the other reasons. We knew the project. But also, we thought, how can we design and advocate for urban living if we don’t do it ourselves?

The first 15 years were nice because we knew our neighbors. We sort of grew up together. Over the last eight years or so, it’s become a little more transient. 2008 was the bubble. That’s when a lot of people lost their homes. The ones that didn’t lose their homes, a light bulb goes off, and they think, “If I’m underwater, if I’m upside down, I can lease my house out.” We get people from the dental school and medical school – a lot of medical students – renting here.

Four years ago, our son was going to school, and I was planning to step away from the company and do my own thing. I said to my wife, “Look, let’s go wherever we want,” and my wife said, “Nope, we’re staying.” So, we invested in the kitchen and bathrooms, and we’re here to stay.

My wife Jennifer (Coleman) and I have a general rule – if we can’t find a business that we need in this neighborhood, we stay in the city of Cleveland. You have Rumi’s Market up there. The Playhouse, when they used to be open, had a restaurant that we used to support. We try to support the shops next door (Church Square). I very rarely have to go up the hill or go out west to go shopping. Ironically, there’s still stuff inside the Clinic you can go and utilize, like the farmers market. I try to support culturally significant black and brown businesses, through my work and also through my commerce.

It’s starting to come together. We have Angie’s Restaurant, Dunkin, Souper Market. We go to University Circle. I just wish there were more amenities within a quarter mile. There’s a couple of places on Cedar that still exist that we try to support.

Over the years, the relationship with the Cleveland Clinic has changed. I’ve criticized and critiqued them for a long time, but for a project that I was involved with in Fairfax, The Aura, the Clinic came to the table. They assisted in land acquisition, brought $10 million plus in gap financing, which I think is an excellent model. I hope that continues. It happens in other cities – for example, Baltimore with Johns Hopkins, in Columbus with the Children’s Hospital, has the same sort of model.

There are some opportunities we’ve fallen short on in this neighborhood. There are a lot of politics and power struggles around the Opportunity Corridor. There’s no reason why every square foot or acre of that boulevard shouldn’t be full. I know how we get there. I just don’t know who’s going to broker it. My simplistic brain says that University Hospitals, Cleveland clinic, the two medical schools, the institutions, the art museum – they all have supply chains. They have agency. Why do you think IBM is sitting there (on Cedar Avenue)? They have their regional repository there. These institutions have the ability to cause some of these businesses to set up shop here (on the Opportunity Corridor). To me, proximity solves part of the problem. You’re not shipping stuff in like dry cleaning or janitorial supplies.

It also wouldn’t be the end of the world if some of those Starbucks weren’t within the four walls of the Clinic. I’ve been looking at what happens at, for example, at the University of Wisconsin – there’s a community college of 50,000 plus, a university of 50,000 plus, and they actually work together to create startup businesses. There’s a few million square feet of businesses that exist. There’s a lot going on in this city, but I just don’t know how you convene and create businesses along the Opportunity Corridor.

The administration change is why things have changed at the Clinic. In prior years it was Toby (Cosgrove). Now you have (Tom) Mihaljevic. As soon as he walked in the door, there was a big town hall meeting. That was a few years back during Covid. They’re actually sharing plans now, which has come a long way, because they used to hide behind a curtain and kind of show up and say, “We need a permit.” They’re trying. I think they’re doing more than just telling this neighborhood through screenings that we have health disparities – because it’s like, “OK, what are you going to do about it?”

In my opinion, their health care philosophy should be that community development and engagement is a form of health care. The stresses that we see and encounter as people who live in this neighborhood when you’re building these big billion dollar buildings that aren’t for us, that is a real stress. So, I would hope that the next wave of engagement includes creating a front door, both literally and figuratively, for folks coming to visit this institution.

Right now, it is so auto-centric. But when I walk some days, in the morning, sometimes in the evening, I see there’s a lot of pedestrians that work here that need to get to and fro. Is it a crime to see a donut shop or a coffee shop from a public right of way? Is that a crime? You need to activate the pedestrian realm. The allay, the reflecting pond at the Clinic, you notice there are no benches there. I remember walking my son there, and there was no place to take a respite, if you wanted to sit down and enjoy nature. The benches at the medical and dental school, they’re such a rigid and hard environment. And people won’t use those types of environments unless they feel comfortable, unless it’s inviting and engaging. Those areas very seldom get used.

With these last few buildings they built on Cedar, they’re trying to create an environment where people feel comfortable, what they call rooms, with pockets of benches and landscaping. If they don’t create an environment where you and I would feel comfortable, why would people who work there utilize it? They won’t. We need to create an environment that will attract and create talent, too. I’m not talking just doctors, but also researchers and innovators, young people. They’re not just looking for a gig.

We’ve come a long way, and there’s no reason to believe the Clinic won’t continue doing that.

But there’s the downside to progress. Prices go up. And that’s gentrification. Property taxes go up. As much as Fairfax tried to be intentional with development at E. 105th, unfortunately you’re getting investors buying houses, putting lipstick on a pig, and trying to sell them for a profit.

Fairfax is probably one of the easiest neighborhoods to get to from a public transportation standpoint. What’s amazing and what people don’t realize is the access to buses and the Health Line. If I were looking for a place to live I’d be like, “Wait a minute, if you look at the amount of jobs in this area available that are walkable …” Within a mile or less you also have access to some of the best food in the city, whether it’s Little Italy or University Circle or you want to hit some of the urban joints. You have access to health care. You have access to gardens and museums and you’re not too far from hitting the Towpath if you take the Opportunity Corridor paved pathway and E. 55th, which dumps you down there. From a biking standpoint, pedestrian standpoint, public transportation standpoint, and employment standpoint, I don’t think you can beat Fairfax. There’s no other place like it in the city.”