Robert L. Render III is a proactive, innovative leader renowned for his civic contributions and

community engagement. With a robust background in fundraising and outreach, he excels in

cultivating relationships across civic, business, and political sectors. Known for his exceptional

interpersonal skills and visionary outlook, Render conceptualizes and delivers impactful projects

within budget and on time. His career highlights include roles as Ward 6 Precinct Committee

Member, Executive Board Member of the Cuyahoga County Democratic Party, and President of the East 128th Street Block Club Association. Render’s commitment to public service is underscored by numerous awards, including the Senior of the Year Award and commendations from the Ohio House of Representatives. A veteran of the United States Air Force, Render brings a resilient, solutions-oriented approach to every endeavor, aiming to leave a lasting positive impact on the communities he serves.

My mother was from Montgomery, Alabama. She came to Cleveland via Chicago. My father, on the other hand, came out of LaGrange, Georgia, which is where Otis Moss Jr. (former pastor of Olivet Baptist Church) and his father and grandfather came out of. I was born out of wedlock. My mother and father were not married. He had a business on the corner of 100th and Quebec. Right now, it’s a vacant lot. He had his own store, and upstairs there were apartments where he and Nancy Render lived. We lived in one of his apartments on East 105th Street. My father put my mother and I up in one of his units.

My father’s wife for whatever reason couldn’t have children, so Nancy came to my mother to purchase me. She offered her money to turn me over to her, and my mother wouldn’t do it. Nancy knew that Bob Render Jr. had me out of wedlock, because I looked exactly like him. I was just a kid, 2, 3 years old.

My old man used to work for the railroad, somewhere out of Collinwood. A lot of Black folks worked out of Collinwood. He got into it with someone. This was how the story was told to me. My father was fiercely independent. He was a racketeer (a type of organized crime), and he stopped working for anyone, because he said, ‘I’ll have to kill one of them mother—.” He started his own business, bought property, ran his own store, did the numbers, and was a racketeer. So yeah, he knew the Italians. Our part of Fairfax was different. You had a mixture of Italians and Blacks.

Blacks and Italians fought all the time in Collinwood, but that was not the case with the Italians who came up where we lived on E. 105th. Most of the Italians (in Fairfax) came up in what we now know as Woodhill. That was all Italians. We came up with the Italians, and we’d have our little fights and run-ins but by the time the week was over, you was staying at their house or they would spend the night at your house and y’all was friends again. Racism was still there but it wasn’t the kind of brutal fighting you’d find out in Collinwood.

My father decided he wanted his kids to go to Catholic school, so he paid the tuition. I went to St. Marion’s, and from St. Marion’s, I went on to Cathedral Latin, and from Cathedral Latin I went to Tri-C, and then I went to the University of Dayton. After St. Marion’s closed, all those kids came to St. Adelbert’s. That church also became the home of the first Black museum in the country, which was run by Icabod Flewellen. His collection is now at the East Cleveland library. Bob Hope was raised off E. 105th between Cedar and Quincy. The Pla-Mor was the roller rink where African Americans came from all over the city, it was at 108th and Cedar.

When we moved from 105th, which was a commercial strip, even though there were apartments and businesses there, to 100th street, we were renters but we thought we were in seventh heaven to move onto a really residential street. Now, if you was really doing something, you moved on 89th street. Folks between Cedar and Quincy, folks would say you was in “high cotton” … they’d say you was “steppin’ in high cotton.” You had really made it if you were on 89th. The unique thing on 89th was the lots were bigger, the houses were huge – in our mind they were like mini mansions. Your really upscale, upwardly mobile black folks lived on 89th. Both parents were working, maybe, but sometimes it wasn’t necessary if the father was a professional. They were doctors, lawyers or maybe teachers.

My mother, her name was Corrie Lee Jones. She married a guy in Chicago before she came to Cleveland. That blew up for a variety of reasons. Then she married Richmond Jones from New York. His brothers lived on the west side. My natural father was in my life for a little while. He reminds me of Don King to some extent. Even though he had me out of wedlock, he found out that his wife (Nancy) was cheating on him. He set it up for him to meet his wife on 100th Street, and the guy she was kicking it with was a well-known entrepreneur himself. He shot both of them. He attempted to kill both of them. Now, the irony was, he was gonna shoot her for cheating, when he had me out of wedlock! And no telling who else he was fooling around with, and I may have other siblings I don’t even know! He shot both of them and then he killed himself, because he was not going to go to jail after he shot them. They got them to the hospital and both of them lived. The funeral (for my father) was at Boyd Funeral Home.

He was very authoritarian. People were afraid of him. He was very abusive. Back then, if there was a domestic problem, the police weren’t going to get involved, you just worked that out, between you and your spouse or your significant other. My mother was just fed up, so two weeks before my father shot Nancy and I think Toby and killed himself, she said I think we’re going to go to New York. She was going to get out of Cleveland. She had figured out how she was going to do it, she had saved the money, and was going to leave town in the middle of the night, take me, and she’d be gone. Two weeks later, he was dead.

I went to the funeral. I vaguely remember it. I was three, four years old. He had an awful lot of resources. I remember him having a scooter. He would take me on the scooter. And I had all these toys. I don’t know who angered him or made him mad, but he took all the toys and threw them away and bought all new toys. I remember him having an Oldsmobile. He had all the things that were popular then because he had the resources to do all that. But everybody was afraid of him. My aunt would tell me, your father was something else, he would either pistol whip you or he would shoot you.

When we left 100th Street, people thought we owned the house. My parents, Richmond Jones and my mother, took care of that house, and they thought we owned it. We moved to Ludlow. When I came out of the military I gave them enough money for a down payment on a house, because they rented all the time, that’s how we ended up in Ludlow. But I eventually was able to buy the house that I grew up in at 100th and Cedar, I still have the house now.

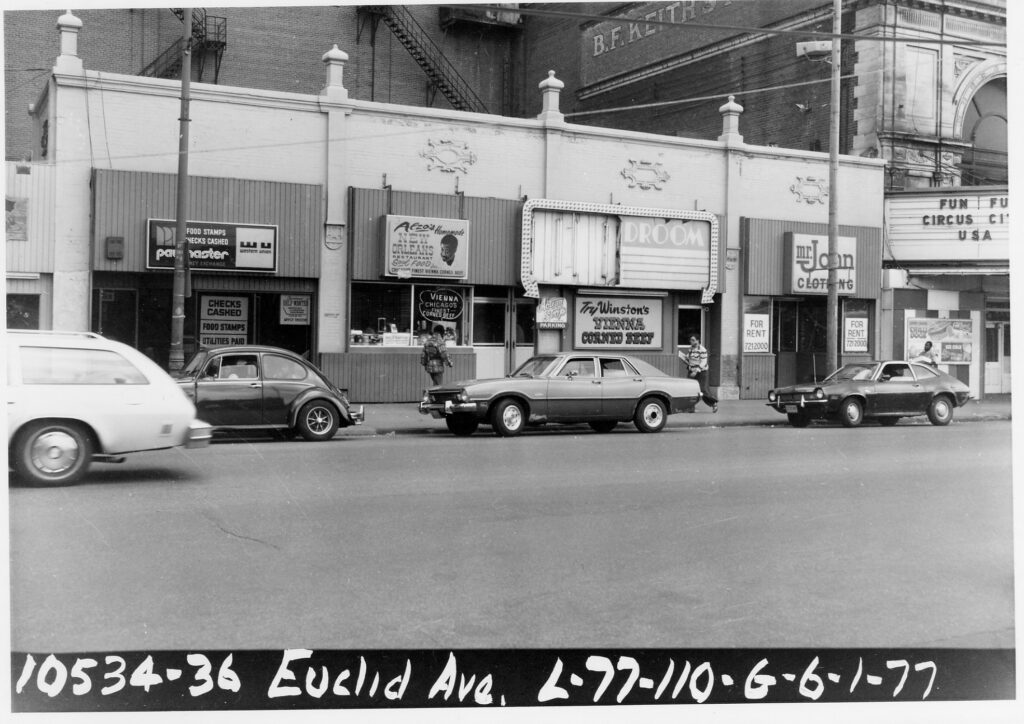

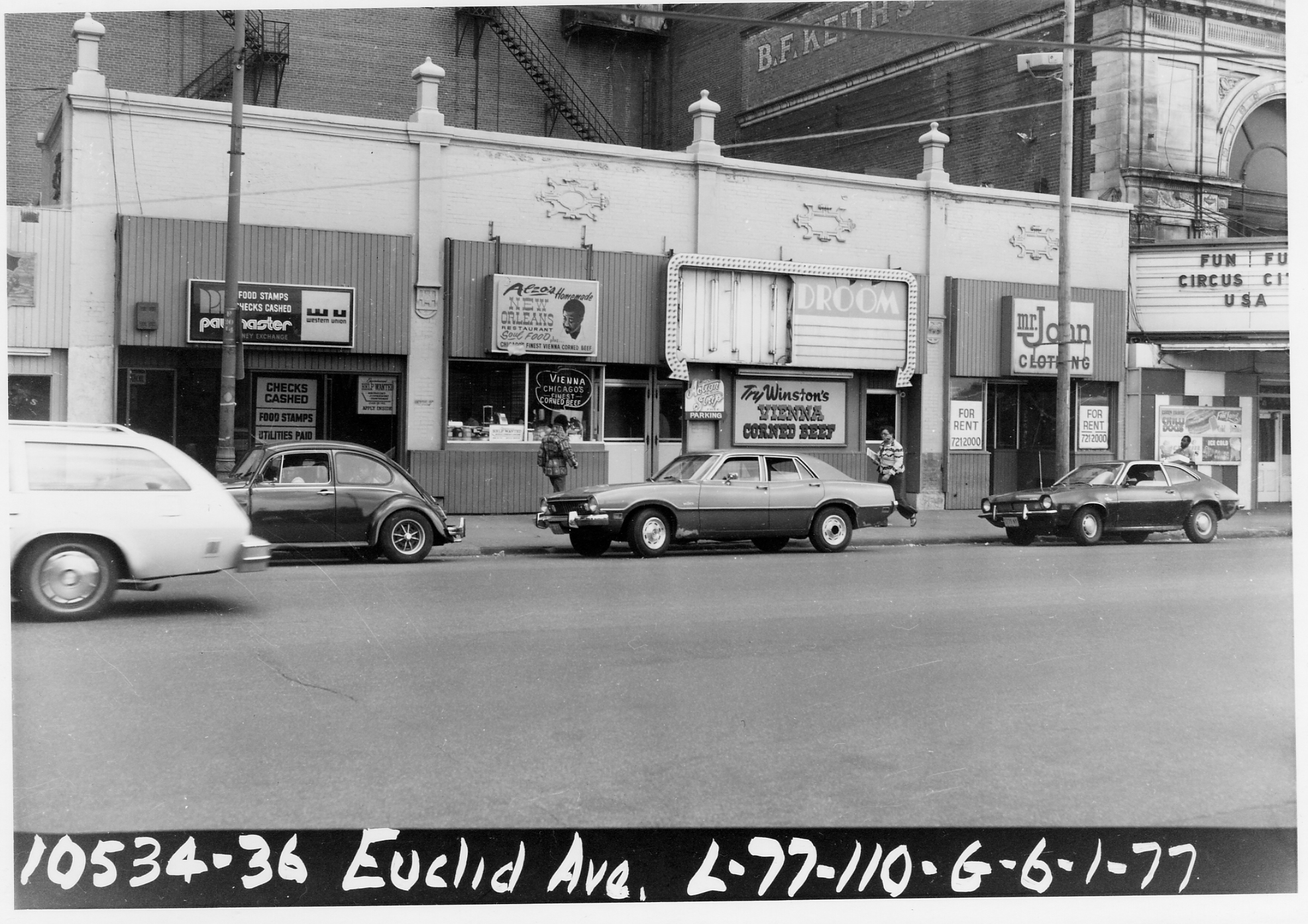

There was no such thing back then as food deserts, we didn’t live in food deserts, as you know them now. Because you could go anywhere and get fresh fruit. There was walkability, like when your grandfather was here. Most people didn’t have cars, and those who did were fortunate to have cars. But there was walking. You had public transportation, trolleys and the bus, and you could walk everywhere. It was safe, it was cohesive, family members lived all around you, aunts and cousins close by in the neighborhood. There were a lot of Black owned businesses in the neighborhood. You didn’t have to go downtown, and if you did go downtown to May Company or Halle’s or Higbee’s or Sterling Linder, that was a treat. But it wasn’t necessary. You know, everything was either on Cedar, Quincy, or 105th. And I mean everything.

My mother got a job at Cleveland Clinic eventually. When she got hired at the Cleveland Clinic there was only one building. On 93rd and Euclid, think about it, one building, that was it, that was the total footprint! By the time she retired, maybe 40 years later, the Cleveland Clinic was already well on its way to becoming a city within a city. The Cleveland Clinic was already buying up parcels of land as they became available, parcels of land south of Cedar, long before we knew. My mother said she always heard there was a 10-year plan, every 10 years they would update that plan. Back in the 70s they already knew they would go all the way down to 79th, all the way over to what we now know as Woodland, and Quincy eventually. But there was an unwritten agreement that the Cleveland Clinic would not go south of Cedar nor north of Chester. As soon as Arthur Woods passed and Fannie Lewis passed, now you see Cleveland Clinic expanding north of Chester and south of Cedar. They had already quietly started acquiring property. There is what I call a subtle anger, it simmers, it’s been simmering for decades. I think the Black community has always been angry with the Cleveland Clinic. In the past, they were not good neighbors. One of the notorious things when we were there was that the Cleveland Clinic’s emergency room was so small you didn’t even know where it was. You didn’t know where the emergency room was, and they would tell you if you don’t have insurance you go to Metro or you go to UH (University Hospitals). They were notorious for that. I think under the new president (Dr. Tomislav Mihaljevic), I’ve seen things I never saw even when my mother was working there. He actually has been in the neighborhood, he’s walked the streets, some of the doctors employed there, I’ve seen them with Vicki Johnson. They walk the neighborhood to take a look firsthand. That was unheard of. Unheard of.”