William F. Boyd, II, president and CEO of E.F. Boyd Funeral Home. affectionately known as “Pepper,” is a Glenville Tarblooder, attended Michigan State University and later graduated from Fisk University. He has been a member of Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity for over 50 years. He joined his father in the family business after graduating from the Pittsburgh School of Mortuary Science. He is the oldest child and only son of the late William F. and Mary W. Boyd. Pepper is an avid golfer and bowler. He has been a licensed funeral director and mortician for over 50 years. He is married to LaVerne Nichols Boyd, Esq., the proud father of four and grandfather of eight. Daughter, Victoria A. Boyd is the Manager for the 89th St. facility.

Marcella M. Boyd Cox, vice president and chief of community engagement for E.F. Boyd Funeral Home, is the youngest daughter of the late William F., Sr. and Mary W. Boyd and the mother of two. Marcella graduated from Lutheran High School East and was inducted into their Hall of Fame. She attended Baldwin Wallace College and Cleveland State University. Marcella became a licensed funeral director in 1988 and was appointed in September 2017 by Gov. John Kasich to the State Board of Embalmers and Funeral Directors where she served until March 2019. She is a member of the Cleveland Chapter of Girl Friends, past president of the Greater Cleveland Chapter-Top Ladies of Distinction, Inc., National Coalition of 100 Black Women – GCC, 100 Black Women of Funeral Service, Buckeye State Funeral Directors, Legacy Life member National Council of Negro Women – Cuyahoga County Section, Cleveland MOTTEP Board member and the Cleveland Drifters. She loves serving the community and families.

Marina Grant, financial officer for E.F. Boyd Funeral Home, is one of two daughters of the late William F. and Mary W. Boyd. She joined the family business in 1982. Marina, along with her brother, Pepper and both of her parents, is a Glenville Tarblooder. She is an active member of Forest Hill Church and former Board member of the Hospice of the Western Reserve, African American Auxiliary. She is also the proud mother of four and the grandmother of thirteen. Daughter, Lisa Boyd Hamilton is the Advanced Planning Manager and Emery Chapel Manager.

MARCELLA BOYD COX

My grandfather, Elmer F. Boyd, opened his doors in 1905. He had a couple locations on Central Avenue that were storefronts. I believe one of them was half haberdashery (a men’s clothing store) and half funeral parlor. Before that, he was a coachman, and he also had a barber shop. He took care of the horses on the west side.

MARINA GRANT

He was born in 1875. He came to Cleveland from Urbana, Ohio in 1898. He was a pullman porter on the trains. At that time, at the turn of the century, there was not a lot of occupations for black people to go into. There was either preaching, teaching, or undertaking. So my grandfather decided to become a funeral director and serve his people. I believe he was motivated by his mother’s death.

WILLIAM PEPPER BOYD

There were three funeral homes in the area, which was growing slowly at the time. Basically, at one time, all the African Americans lived below 55th Street.

MARCELLA

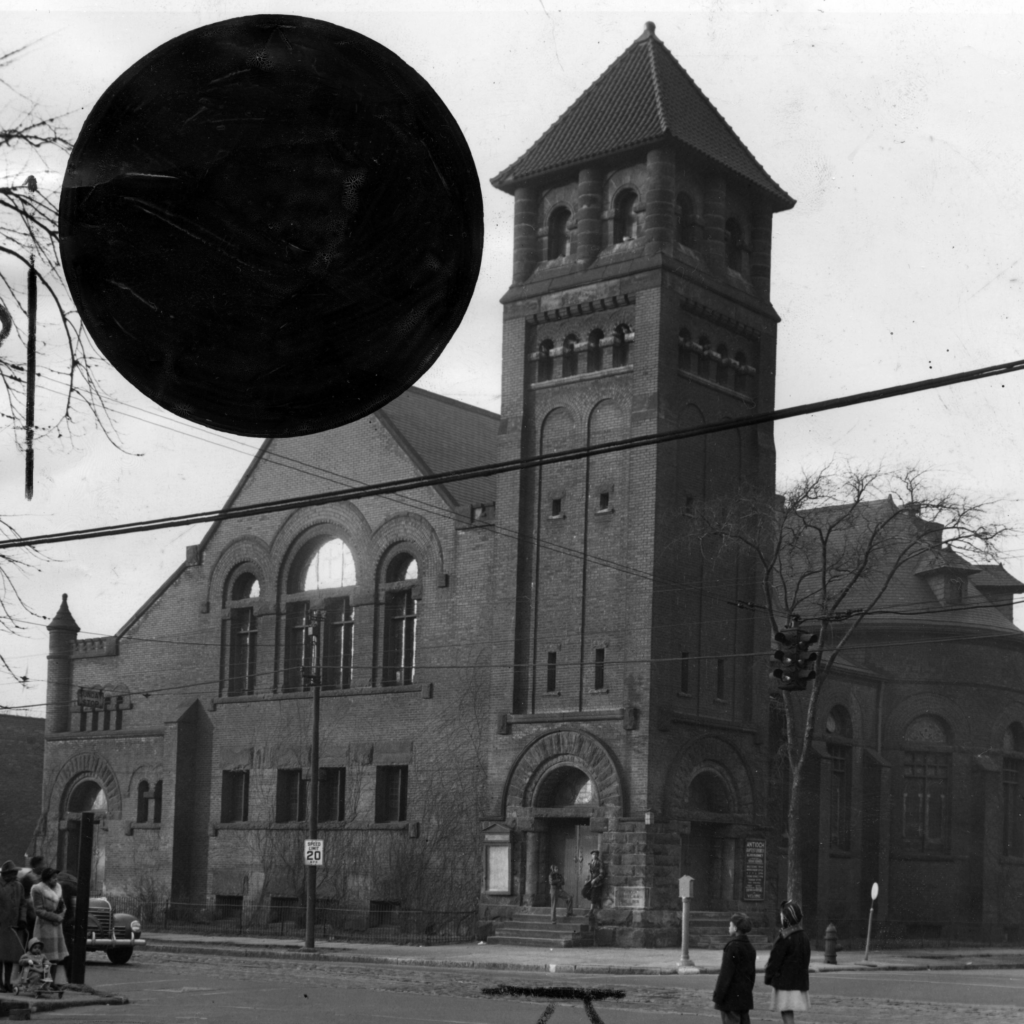

He was a quiet individual, but he was very highly respected. My grandfather was also a member of the first African American Episcopal Church here, St. John’s, which is down on 40th. And in those days, people were very religious and attended church regularly. They were very involved. My grandfather and my grandmother were very, very big parts of the church. My grandmother was a member here at Antioch.

PEPPER

He had a funeral home right around the corner from St. John at 43rd and Central. They had a guy named Big Barry who was over 750 pounds. They had to take the doors off the funeral home to get him in. Then they used a flatbed to take him to the cemetery. He was a very large man.

I would assume he moved (further east along Central Avenue) because it was a better neighborhood. People were starting to move east. And so he just moved from 25th to 43rd. And then eventually, they came out here (to the Fairfax area). I’m sure it was also a larger building. The business moved to Fairfax in 1938. They bought the building from Slaughter Brothers (Funeral Home) when they went under.

One of the things that made it successful is you had a big population shift. You had this tremendous migration from the south, and you had just a couple of funeral homes to service the population. It got to the point that we were going to only white funeral homes, and somebody thought, “Well, maybe we need to get our own.” They saw the need and there was a migration, so it was a larger population.

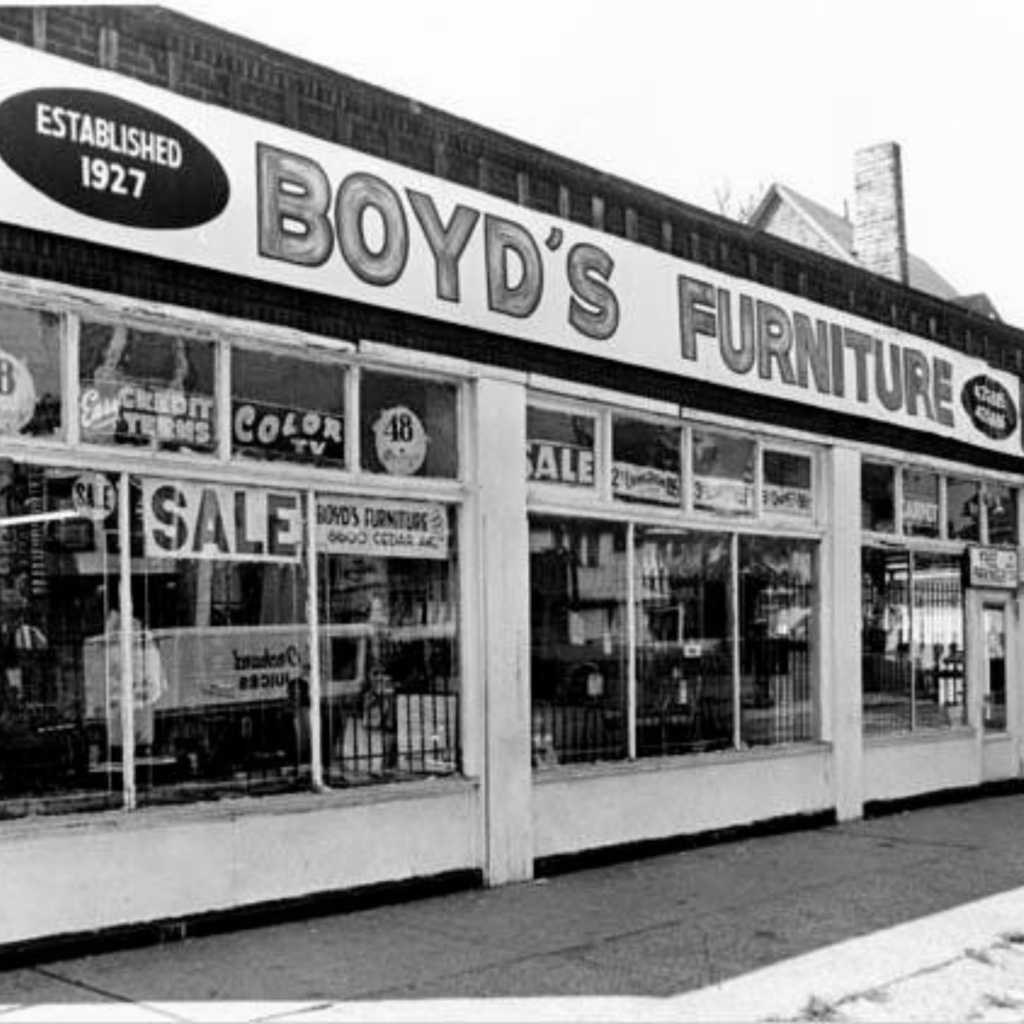

The Fairfax area was European. Then Blacks started moving in and Europeans started moving out. I think that this area at one time had close to 40,000 people. In the late 80s, early 90s it started really diminishing. But from the 40s up until maybe the beginning of the 90s, you had a melting pot right here. You had Black businesses on both sides of Cedar Avenue, all the way to 105th, all across 105th, and all up and down Quincy. Plus you had people who were in the numbers, which supported a whole lot of people in this neighborhood, because that’s how they made their income or how they fed themselves.

They were racketeers. This is where the lottery came from. People survived. They had numbers, and they had policy. Those were two different businesses. The numbers they would pick up off the Wall Street Journal, and then that would be the number that would be for today. For policy, they had balls they would roll. My father used to call it “sick and accident.” It was “sick” if you missed it, “accident” if you hit it. I had people that worked here, and after work, the first thing they did was go to play policy, and they’d have dimes, nickels, pennies, playing numbers every day. They got six to one, so if you put in $1, you got $6 for your $1. It was just survival. And it was fantastic.

MARINA

That’s why the lottery came out because it was making a lot of money. The state wanted to take it over.

MARCELLA

Racketeers did fund different businesses, because Blacks couldn’t necessarily get bank loans. They would rely on racketeers. That’s just the way it was. That’s historic.

PEPPER

That was the main reason Quincy Savings and Loan started. It supported a whole lot of Black businesses around here because they couldn’t get loans from Cleveland Trust at the time.

It was a thriving neighborhood. I remember there was a German lady over here that had a chicken area. You went in the back, and they’d have cages of chickens. When you wanted a fresh chicken, she’d go over and grab this chicken and put it in the bucket. She’d snap its neck, bring it, and put it in that bucket. Those legs be doing like this (wiggles hands) and I’d stand back like, “Whooo!”

MARCELLA

You had the Fairfax Rec Center. Friday nights, they had family night and I would go with my friends. I can remember, people taught their kids to swim over there.

My grandfather and my grandmother lived upstairs. He passed in 1944. My grandmother and her sister and her niece lived up there.

PEPPER

The neighborhood changed because of integration and busing. That changed a whole lot of things. I had a cousin that moved out in Mount Pleasant, and they painted his whole house in different nasty words. At the time, it was basically confined – you had most of your blacks from here over to St. Clair.

MARCELLA

You had a lot of Jewish people here, too. The migration started here around the 30s.

PEPPER

We used to take people to the house. They’d be embalmed at the house. They had all this ceremony at the house. We’d have to take lamps and the body and the casket to the house, where they’d had their wake and their services. Then the funeral home idea started growing where you could have your families and casket and viewing and everything at a separate place outside of your home. But at the time, people would just awaken, and they would sit in that room with that deceased all day and all night. They’re talking about bringing that back. They’re talking about having people taken back home for services again. It’s a big circle.

MARINA

Everything that goes around comes back around.

PEPPER

Cleveland Clinic is one reason we’ve stayed here so long. They were a big savior. They build and they build and they build. Now, people are looking for homes that are close. Opportunity Corridor is going to be a dynamite situation. People who live in the Heights are buying houses here and turning them into Airbnbs. There’s a slow move back over here. When you’ve got tens of thousands of people working for the Clinic, people are looking for places to live.

MARCELLA

It’s been a saving factor, yes, but the Clinic hasn’t really been attached. The thing you hear about the Clinic is that they’re just not engaged in the Black community, but I think that kind of philosophy is changing. Because they were here it felt a little safer. It wasn’t like you were really in an impoverished neighborhood because they had all that building over there. There’s been discussion about people hoping that they don’t just take over this whole area. But there’s gonna be a lot of building going on. You see things coming, and people want to be close to their jobs, so they’re not not paying that gas or whatever. They’re coming back. It has stabilized the area.

In terms of the Fairfax Market, I think it’s nice, but can the community support it? That’s my first concern. They’re talking about all this development that’s going to be done here. What’s going to happen to the people here who are going to get priced out who won’t be able to pay the rent? The apartment building above the market is nice, but it’s not serving people in this neighborhood.

PEPPER

The only reason they built this grocery store was to serve people who work here, not the people in this neighborhood. But it’s really a nice place. They’re building three and four hundred thousand dollar homes in this area now.

Since 1905, we’ve gone from three funeral homes to 20-some African American funeral homes. People that were isolated are now moving everywhere, and with that, you don’t have the same concentration. That was one of the reasons that we got a location out in Warrensville Heights. People are living everywhere. Before, you were isolated, and then integration and busing opened it up. In a lot of cities, you go with what’s closest, but we still get support here.

MARCELLA

We have that reputation. We have quite a legacy and a commitment to the community. This community is always about giving back. It’s a community related business, a people related business. We give back by being members of the community, contributing to the welfare, trying to do the best we can by people and still offering a good service.

PEPPER

I’ve spent all my whole life basically right in this neighborhood. I’ve been working here for almost 60 years. So it’s a part of me – the building is a part of me. The neighborhood has changed, that’s true. You used to be able to just walk around and see people all the time. People moved out. Properties started going down. This is going to happen until these corporations come in and reinvest in here. Eventually, it’s gonna level off. You’re going to see a trend of people moving back into this area. I think it’s still a very viable area. There’s a lot of things you can do, and you can get some pretty good deals on property. You’ve got the Clinic, Case Western, and University Hospitals nearby. You’ve got three big players right there.

MARCELLA

Then you’ve got all of the building that’s going on. There are a lot of people who’ve been here a long time and never left. Families we’ve served for years. They’re still here.

PEPPER

You hear people say, “I’m not going to move to Aurora now. I’m going to invest in my property. I’m going to come back in town.” It reminds me of Washington, D.C. years ago. You have white people moving into Black neighborhoods.

There used to be seven hundred, eight hundred thousand people living here. Now it’s under four hundred thousand. But this is a really great town. You go to New York, it’s like gridlock. Here, you can get around, you can get home in 15-20 minutes. There are a lot of positives. They’re talking about developing the waterfront, improving downtown, and getting people involved. There’s going to be some really good things that are going to happen in this town. It’s going to take a little while, but it’ll come back.”