By John Perse

Ballots and Bullets, by Cleveland attorney and author James Robenalt, is a fascinating and in-depth account of the Glenville Shootout and the subsequent riots in July 1968. In many ways, the book reads like a novel and in others, like an investigative report of the lead up to, and aftermath of, those tragic days in the summer of 1968. The book is particularly adept at focusing on the specific details of the events of that time, in an almost minute by minute sequence, as well as providing a keen analysis of the overall national racial, economic, urban, and historic trends leading up to that one specific day, July 23. Particularly insightful is the way Robenalt weaves together the specific milieu of Cleveland in 1968 within the larger national context of the tumult of the mid- to late-1960s in America.

That Cleveland exploded in what can only be called racial urban warfare on the streets of Glenville on that hot July day should come as no surprise when set within the overall context of America in 1968, and in particular, the emerging trends of the civil rights movement and the rise of Black Nationalism. Indeed, the Memphis Sanitation Workers strike, the violence in Orangeburg, South Carolina during a civil rights protest against a segregated bowling alley, the takeover of an administration building by Black students at Howard University, and of course, the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King on April 4th, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee, could only be considered a foreshadowing of what was to occur in Cleveland later that summer. In fact, just two days after King’s assassination, a 90-minute shootout between Black Panthers and the police in Oakland, California took place. All told, Robenalt captures the realities of how and why the civil rights movement was becoming increasingly militant and confrontational at that time.

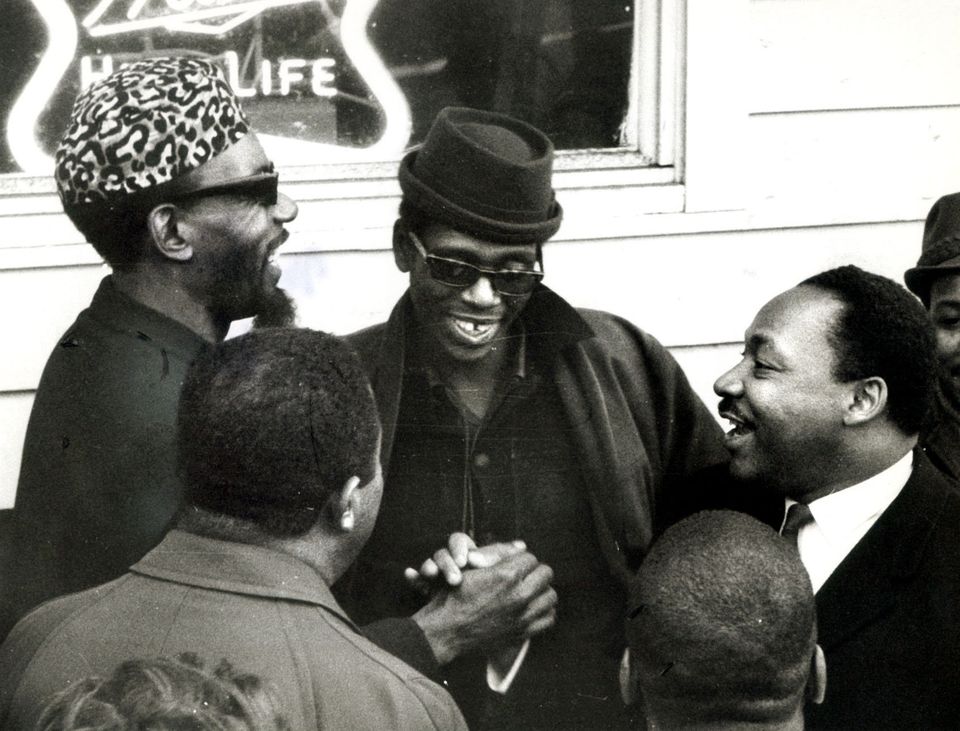

We learn that Cleveland itself was becoming a center of the civil rights movement in the 1960s, too. Indeed, Martin Luther King had visited Cleveland on numerous occasions going back to the mid 1950s, and none other than Malcolm X came to Cleveland where, on April 13, 1968, he gave his famous “Ballot or the Bullet” speech at Cory United Methodist Church on East 105th Street in Glenville. To Roebnalt, it should not have been a surprise that the larger national civil rights movement and the specific events in Cleveland in the summer of 1968 would have resulted in an armed conflagration. Robenalt describes that even with the election in November 1967 of Carl Stokes as the first Black mayor of a major city, the deep-seated and long simmering frustrations of Cleveland’s Black communities, coupled with the impact of the rise of Black Nationalism, could not forestall the events of July 23.

Robenalt’s book is especially impressive in terms of the detailed backgrounds of the key participants in the larger civil rights movement, as well as the specific, and at times, excruciating details of the actual Glenville riots. Interwoven throughout, Robenalt sheds light on the larger issues of the fight for equality related, as it was, to educational, economic, political, and urban affairs.

In a new afterword to the original book, Robenalt articulates, clearly that the issues that led to those horrific days in July of 1968 are still unresolved today. Continued problems with police actions, responses to those police actions, and deep-seated systemic racial, housing, educational, and economic realities, continue to plague Cleveland. He also elaborates on the current polarization in America and links together the massacre against members of the Hispanic community in El Paso in 2019, the heinous attack on the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh in 2018, and the deadly Unite the Right Rally in Charlottesville in 2017.

In this manner, Robenalt connects the events in Glenville in 1968 with the issues confronting America in 2024. He ends the new afterword in a cautious yet hopeful note when he says that the only answer to these issues “ . . . is for people of goodwill . . .to continue to see the human struggle as one struggle and to engage in dialogue, however uncomfortable that may be.”