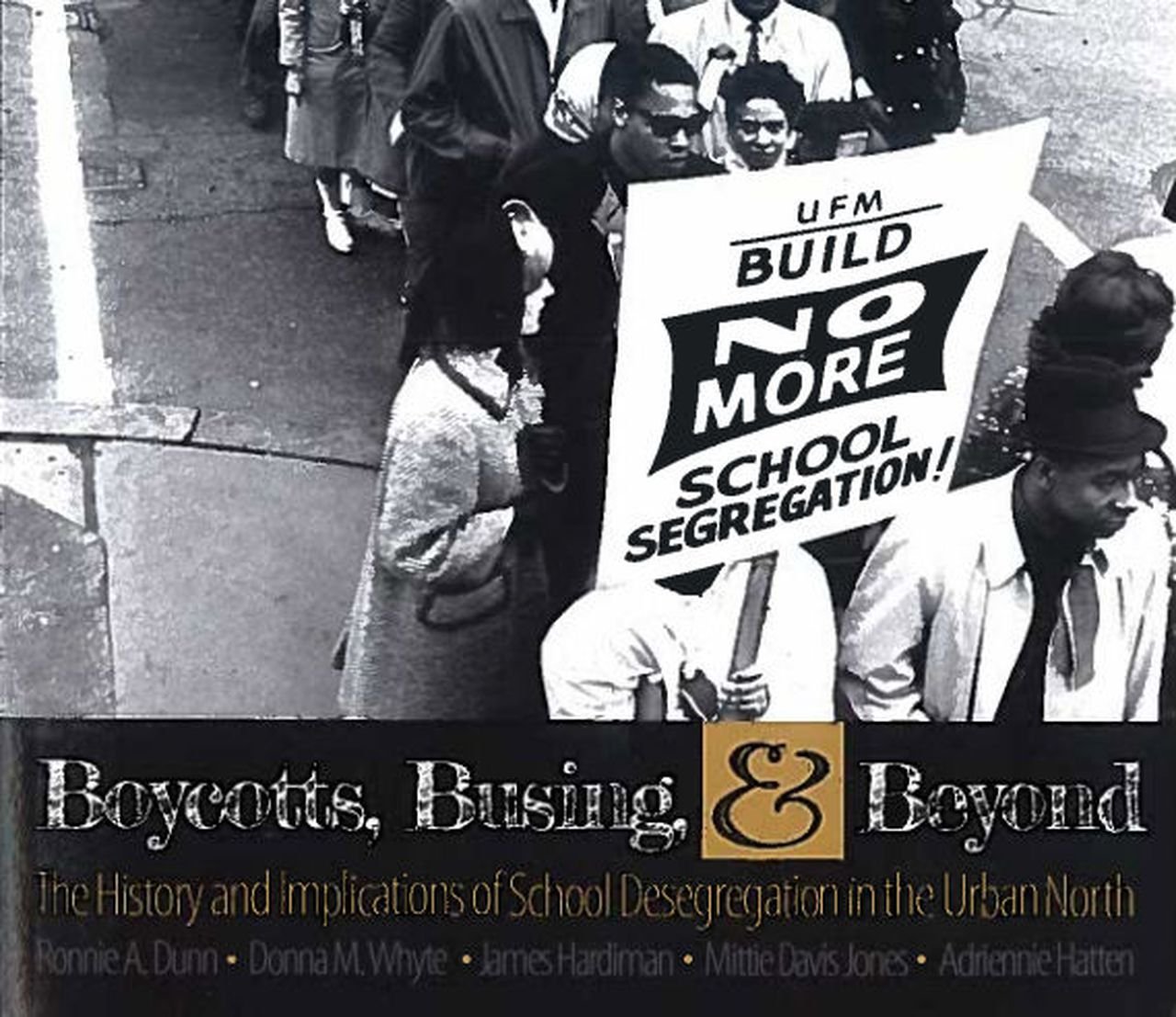

Boycotts, Busing, and Beyond: The History and Implications of School Desegregation in the Urban North by Ronnie A. Dunn, Donna M. Whyte, James Hardiman, Mittie Davis Jones, Adriennie Hatten

Having lived most of my life in the Cleveland area, many people I know have shared with me their basic narrative about school desegregation in Cleveland in the 1960s and 1970s. According to them it was simply a disaster that led to the downfall of the Cleveland schools. The decisions and remedies handed down by Judge Frank J. Battisti (including the dreaded “forced” busing) have led many to assert that the legal battles and subsequent policies which attempted to desegregate the school system made things worse.

Thanks to an incredible team of experts who wrote Boycotts, Busing and Beyond (2016, Kendall Hunt Publishing), anyone who wants to learn more about the Cleveland schools before, during, and after desegregation can learn so much more to challenge this simple narrative. To be sure, this was a complicated chapter in Cleveland’s history.

First, some numbers: between 1940-1950, Cleveland’s Black population exploded from 85,000 to 148,000, and most Blacks, many of whom were subjected to redlining policies, were living in overcrowded, segregated housing on the city’s east side. In 1950, nearly 60% of Black students in the Cleveland schools attended schools that were 91-100% Black; by 1965 that number had jumped to almost 79%. Likewise, in 1961, 80% of white students attended schools with 0-10% Black student populations.

Given the fact that Blacks lived in segregated areas, the Board over decades made choices to maintain racially segregated schools. In 1943 the Board chose to add temporary classrooms at Gracemount Elementary, which was 100% white, when nearby Beehive (34% Black) or A.J. Rickoff (11% Black) had available capacity. In Hough (a neighborhood that became predominantly Black by 1960), as a way to address severe overcrowding in Hough neighborhood schools, the Cleveland schools sent some students to the equally crowded Wade Park school (a predominantly Black school) – and ignored sending them to underutilized white schools just outside of Hough.

Beyond the numbers, the book examines the policies the Cleveland school board undertook to address the demographic changes impacting the district, from relay schools (Black students would attend school for half a day to accommodate overcrowding) to “intact busing” – transporting Black students to predominantly white schools that were underutilized but prohibiting Black students from eating lunch in the cafeteria, attending assemblies or gym classes, or participating in school-wide extracurricular activities. Addressing these policies became complicated, too. Attempting to quell problems, Paul Briggs, when he became superintendent in 1963, shifted the Board’s focus from integration to quality education in each school, mainly because significant numbers of Black families supported it. Eventually, the NAACP developed their own Cleveland Plan but felt the Cleveland School Board dismissed their ideas. The lawsuit the NAACP filed against the district barely passed an internal vote because of significant disagreements among members.

The book details so much more for anyone wanting to understand this complicated era in Cleveland. It also provides a history of Black education in the U.S. as well as industrialization and Black migration to Cleveland in the early 20th century. James Hardiman, one of the authors and the lead attorney for the plaintiffs in the Cleveland school desegregation case, describes the specific evidence of Cleveland schools’ practices leading to the 1973 lawsuit and the details of the federal court’s remedies to address the segregated district. The book also explores the legacies of the legal battles over education and over the Cleveland schools in particular.

Boycotts helps make sense of the details and contextualizes the educational landscape as thousands of families experienced it. For anyone who wants to work toward possible solutions to the inequities of the educational systems – in Cleveland proper, its suburbs, or throughout the state of Ohio – this work is required reading.

-Greg Deegan