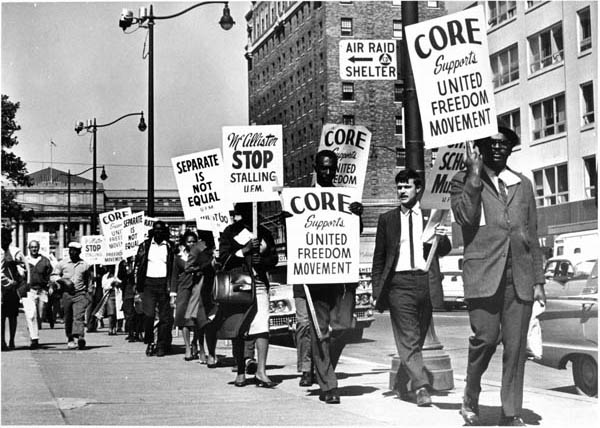

Members of the Congress of Racial Equality participate in a United Freedom Movement demonstration in Cleveland, Ohio, 1965, via Harambee City Archives

By John Perse

Harambee is the Swahili word for “let’s pull together.”

In so many respects, the title of Nishani Frazier’s extraordinary history of the Congress of Racial Equality, Harambee City: The Congress of Racial Equality in Cleveland and the Rise of Black Power Populism, fits perfectly.

Frazier’s account captures the massive efforts and sacrifices that Black community members and activists collectively undertook in the name of equality and opportunity for Black Americans in Cleveland and throughout the U.S. Her book title is also ironic, given the astonishing number of divisive struggles within the Cleveland chapter of the Congress of Racial Equity (CORE), the larger national CORE organization, and the civil rights and freedom movement in general. Indeed, Frazier’s eloquent and extremely well researched history covers the period when the civil rights and freedom movement were at a crossroads.

She details from archival research and personal observations (many of Frazier’s close relatives and family friends were directly involved in CORE) the evolution of CORE that resulted in – and was the result of – the evolution of the overall civil rights movement. As Frazier writes “Sometime after 1966 and the declaration of Black power, CORE drastically changed its image. Those transformations raised uncomfortable questions about its relationship to Black power and ran afoul of the organization’s construction of its origin history. And yet, it proved a pivotal period for CORE as it navigated the changes in the freedom movement, attempting to innovate and transform the political and economic lives of the Black community.” (pg. xxix)

We read about Frazier’s very involved mother, who often expressed anger with Roy Innis, who became CORE’s national chair in 1968. “‘There ain’t no doggone CORE. Fool!’ My mama was standing with hands on hips yelling at the television . . . screaming at the screen version of Roy Innis. Again. It was something Pauline Warfield Frazier was apt to do anytime her eyes set upon his feature . . . Her opinionated outrage inevitably led to a litany of charges and emphatic declarations. ‘CORE gone!’”

In Cleveland, the local leadership accused Innis of not sufficiently addressing the concerns of African Americans in the community and being too willing to compromise with government entities.

The reader can also gain a broad understanding of the CORE movement from its early history to its philosophical evolution, and the divisive issues that strained the organization. The book shifts back and forth in an analysis of the relationships between the national and local chapters of CORE, the personalities involved and their varying visions, and the perspectives specific to Cleveland.

That the Cleveland CORE organization evolved into a major player in the overall freedom movement and the most militant civil rights organization in Cleveland is discussed by delving into how local and regional perspectives set in the context of Cleveland pushed the agenda “…beyond the boundaries set by the national office.” (pg. xxxiv). All of this culminates in ideas regarding Black power in Cleveland influencing CORE’s national Black power policy.

Nishani Frazier’s work is essential reading for anyone trying to understand the ways in which activists framed and worked to address local and national civil rights issues. Her important work centers Cleveland in the struggle, and it’s hard not to see how relevant these same issues are in today’s civil rights conversations.